Is the Tight Maritime Market Driven by Surging Demand or Capacity Constraints?

US containerized imports have remained consistently high, with freight rates spiking and capacity hard to come by. Where exactly lies the problem?

In all earnestness, Q1 ‘24 acted quite as expected, even with the then-recent Red Sea crisis and the persisting Panama Canal drought. The fresh vessel capacity added into the market by container liners was offset in part by the circumvention around the Horn of Africa, helping steady freight rates even as capacity was relatively easy to come by. Imports remained strong in January, which can be explained by retailer orders looking to restock their drawn-down inventories from the holiday season, just before the Chinese New Year in early February.

Import volumes predictably fell in February, but not by the same margin they used to fall every year. While this should have raised some suspicion, freight forwarders and BCOs believed that prices would still drop due to the increase in global vessel capacity, thanks to the record number of vessels ordered by cash-rich liners at the height of the pandemic.

This expectation led forwarders and BCOs to delay signing their long-term contracts with the liners during Q1 ‘24. The word on the street was to extend negotiations as much as possible, anticipating a continued fall in freight rates. But as April went by and May arrived, shippers realized with growing apprehension that freight rates were in fact not falling but climbing. Consistently high imports into the US sent trans-Pacific and trans-Atlantic rates soaring, with stakeholders believing this to be an early onset of the ‘peak shipping season.’

Consistently high imports into the US sent trans-Pacific and trans-Atlantic rates soaring, with stakeholders believing this to be an early onset of the ‘peak shipping season.’

After a couple of $1,000 GRIs in May and the peak season surcharge kicking in in July, carriers are firmly on top of the market. That said, the actual reasoning behind the unusually tight H1 ‘24 market is still unclear — is this arising supply-side or demand-side?

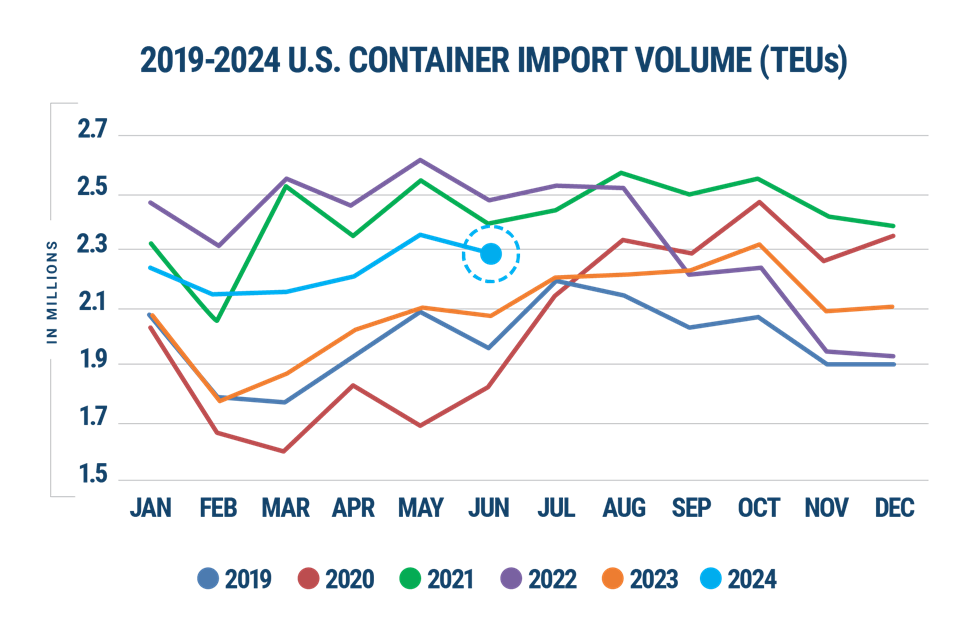

On the surface, the demand-side tightness makes a good case, as H1 ‘24 containerized volumes inbound to the US have remained well higher than H1 ‘23 and H1 ‘19. The years ‘21 and ‘22 were largely anomalies to usual trends and were a clear demand-side problem with businesses shipping record volumes to meet explosive demand.

However, if we look a bit closer, H1 ‘23 import volumes were stymied by existing bloated inventories, which businesses were struggling to sell off. With that context, the year-over-year volume growth shown in H1 ‘24 is the market moving towards the regression line, and not a spike in demand per se.

This brings us to the supply-side issues. As witnessed during the height of the pandemic, logistics snarls start to happen when freight volumes increase above a certain threshold. In the case of the US, anything over 2.1 million import TEUs a month has been a cause for concern, straining port apparatus and downstream operations. This is manifested through increased vessels on anchor, longer berth times, and lengthening yard dwell times.

While this was the primary issue plaguing ports a couple of years ago, the issues have compounded today, with ports of origin (i.e. China and SEA) facing the brunt of the problem. Vessel backups across the ports of Singapore, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and the likes, have been at record highs over the last few months, creating a ripple effect across all major freight corridors.

This situation is exacerbated by vessels getting progressively larger, which naturally results in longer berth times, more empty containers being discharged, and a greater difficulty with repositioning those empties.

“Over the last few months, shippers are frustrated with their freight not being picked up at the port of calls, as vessel operators blanked sails. While this feels like liners taking advantage of high rates, it actually is a result of carriers wanting to salvage their schedule reliability that went for a toss due to excessive queuing across most major ports in Asia Pacific,” said Ram Radhakrishnan, the CEO of Silq, a digital freight forwarder.

Vessel operators were likely forced to skip certain ports due to several reasons. One, they could not afford to stomach delays due to port congestion, two, their vessels were getting full at the origin port due to demand, or three, they could not reposition empties at the right time at the right place.

“Our discussions with vessel operators and brokers tell us that vessels leaving China are not always leaving full,” said Radhakrishnan. “While liners spoke of the empty repositioning problem back during the pandemic, they are choosing not to talk about it today. This makes it seem like there is no space on deck, when in reality, that isn’t always the case.”

While liners spoke of the empty repositioning problem back during the pandemic, they are choosing not to talk about it today.

The bigger question is — why wouldn’t the container liners divulge this information? The answer lies in shipper-owned containers (SOCs). During the pandemic, when the empties problem came to light, it opened space for leasing operators and shipper-owned containers to come into the market, which meant liners lost their pricing power on carrier-owned containers.

“Silq used to get SOC options that were cheaper than the asking rate of carrier-owned containers at the height of the capacity crisis in ‘21,” contended Radhakrishnan. “This time around, carriers do not want to reveal there’s a problem with empties, as they don’t want SOCs to reach the market and reduce the margins they make. Plus, entertaining SOCs would mean added liability issues. By saying there’s no space available rather than saying there are no empties available, liners can play it safe and keep the market tight.”

The peak shipping season inching earlier every year and the alarmingly tight market has created a clear case of FOMO among shippers. This prompts them to buy space a few weeks in advance, making redundant bookings to protect themselves from sailing delays and liners ditching their bookings at the last minute.

Ultimately, these redundant bookings mean that vessels end up realizing they have unfilled space, which they fill at a premium on the spot. “With rates being so high, carriers are not asking their BCOs or freight forwarders to fulfill their quota,” said Aditya Ravi, VP Operations & Procurement for Silq. “This gray area is now being exploited by extra loaders in the market that carriers don’t advertise, who are selling space 1-2 weeks before schedule — in a way that can only be termed as auctioneering.”

These loaders call the space that falls through the cracks as ‘dead freight’ — essentially space that will go unfilled due to shippers dropping out as they have already reserved space elsewhere. “I’ve seen loads from Nhava Sheva, India to New York being quoted for $4k, $6k, and $8k — all for vessels departing one week from each other,” said Ravi. “There is no consensus and it’s a highly competitive environment at the moment. If freight forwarders are facing such issues, shippers would have a bigger nightmare navigating this situation.”

Loaders call the space that falls through the cracks as ‘dead freight’ — essentially space that will go unfilled due to shippers dropping out as they have already reserved space elsewhere.

However, there could be some relief on the horizon. Thanks to fresh capacity being deployed, the China to US West Coast lane is seeing spot rates drop, which will likely bring down the two-week fixed FAK rates as well. The US East Coast rates could steady or witness a slight increase as they continue to be plagued by longer turnaround times around the Cape of Good Hope and congestion at transshipment ports.

That said, the market is still extremely volatile going into Q3 ‘24. Considering all that has transpired in the first half of this year, no conjecture can be backed with absolute certainty. Only time will tell if rates stabilizing (or going down) is wishful thinking.